The Combat Conundrum: how violence actually works in mothership.

Mothership is a a game about rising stress, and that's not just limited to within the mechanics: I could fill the constant rubbing out and rewriting of the stress count on my own ineffable character sheet as I poured over these zines over and over, till the edges of them are rubbed raw (a poor sight for a kickstarter product i waited so long for). But why torment myself to this sisyphean task of analysis? Well - you know - being autistic aside: 'Isolation Kills'. That's the title of my own solo rulesets I have been working on (and distracted from by this) - and when i talk on a solo ruleset I do not mean tiddly handful of oracles and a do-it-yourself attitude, I mean a full comprehensive toolset and informational guide (matching the WOM advice on starting rpgs) that reforms mothership as a robust solo system, for use with pre-existing modules or equipped with generative crawls. Its also part manifesto, highlighting what I want to see from more solo games, and solo rulesets; robust systems, solid procedures, and options to assist adjudication. In all it also makes for a fun challenge, rejigging mothership to work solo, and in a way that does not undermine its puzzle solving or horror. You understand then that I have a deep love for this game, and for the third party community that has arisen around it? Good. Because now I’m going to shit on it - alright alright, I'm joking, I'm critiquing it.

There's a few transparent flaws in mothership (and one many seem to think is a flaw but I do not agree with) but here I want to hyperfocus on one: Violent Encounters. A source of confusion for many, such as Mr Alexander over at his Blog and this discussion thread on reddit, but the discussion, as you’d expect for an OSR-adjecent game, is on fixing, but I don’t think mothership’s procedures to Violent Encounters does need fixing, in fact its up there as one of my favourite systems of “combat”. Its narrative, its tense, it highlights the focus on the horror, while, and most importantly, it prioritises player agency.

But I’m not here to get into the weeds of the hows or the whys, instead I want to go back. When I first heard the confusion on the mothership rules (and if you've read reviews on the system it seems to be one people misstep on a lot) I was extremely surprised. “Am i doing it wrong?” and honestly i wish i did, because that would have increased my game designer ego massively. But I reread the rules, rules simple and short enough to do this comfortably, and ones I was already well acquainted with. Then I got confused, and I reread them again, and again, and… You get the idea. I feel bad for my copies!

But what I found was that to a degree how I had been playing mothership’s violent encounters had been correct - as far as “correct” means “Rules as Written” (RAW). But I had also found the rules to be confusing, under-explained, and even at times contradictory. These things I feel coincide with other factors to confuse a lot of people on how exactly mothership’s Violent Encounters are run.

Then there’s Isolation Kills: I’m aiming to reconfigure a heavy-gm (...sorry Warden, which side-note is the coolest GM name ever after mausritter dropped the ball with not using game-mauster) Violent encounter Ruleset into one that is codified, has clear procedures of play, and mechanically feeds back to the player. This is hard to do when the core rules themselves are confusing, and my original aim of a flow chart based procedure came into the baffling stumbling block of there not already being a Violent Encounter flowchart.

So here is a close read through of every segment, rule and procedure of Mothership’s Violent Encounters, to look at how it works RAW, where the confusion arises from, and in the process construct a flowchart for players and wardens to use at the table, and i can go back to writing my solo ruleset. And if you dont give a fuck about mothership this can serve as a warning to designers on the woes of information inclarity. Or if this is all completely useless, It can serve as part of my TTRPG portfolio…

I thought this would be quick… It’s taken me MONTHS.

—

What is mothership?

Before we start we need to understand mothership's core aims.

- it’s scifi

- it’s horror

This gives us some base assumptions going into the game in regards to Violence.

- Scifi - There may be guns and grenades.

- Horror - There will be monsters who pose a threat and you will likely die.

The horror here is what trips people up the most. I feel the people who this game appeals to most are OSR/NSR nerds looking for a new genre, partly because those are the spaces it's advertised in but also because of its core gameplay style. Those interested primarily in Horror RPGs may be well satiated in other genres, especially in narrative games (such as Dread, Ten Candles, or Trophy Dark or the upcoming scifi-horror Cosmic Dark - All of which may handle *Horror* better)

I discovered the game in its 0e version as a beloved lover of scifi horror. I was practically raised on Alien, The Thing and all the greats classic (WATCH SUNSHINE), and I stuck around because, while I primarily do run horror TTRPGS, mothership is closest not to horror movies or literature but to survival horror video games, one of my other deep loves. (and I do believe more dungeon designs should look at survival horror video games for inspiration. Also the true intersection here is Signalis. Just go play it.)

But mothership is scifi - horror and somekindofOSR, in that order. It utilises an osr-style playstyle but is not harboured to its design principles, nor to any specific system. It uses d100, the classes are different, it has a stress and panic; it draws more on traveller and call of cthulhu than DnD (for the OSR is primarily about DnD). Its resolutely NSR (just as my other favourite darling *into the odd* is, where Mythic Bastionland also has some of my favourite combat rules). This is important to understand that it aims to create interesting scifi-horror ruleset more than stick to a specific design dogma. If I was writing a review (and this is not one!) I would be analysing it on how effectively it conveys its genre aims.

Now let's look at each of the core zines to see what exactly Mothership’s Violent Encounters rules are.

The Players Survival Guide (PSG):

Intent and Aims:

The first thing to understand is what the aim of Mothership’s combat is; Its violence. You might have noticed me referring to Violent Encounters, and that's what that stage of play/story is - Just as there are Social Encounters and Investigation Encounters. Violence in mothership is just another issue bringing down your chance of survival. That certainly makes sense for a horror RPG.

How do we know this?

In the brief introduction to the players on what they can expect in Mothership, it never mentions combat:

“Encounter hostile alien life” does certainly hint at violence however, just not combat. Maybe you don’t fight it, maybe you get ripped apart, or maybe you run away…”escape the horrors”... it's promising an encounter, not a fight.

But it does immediately present combat as one of the core stats:

So this highlights that combat will come up, just not as a pointed piece of play but as something the character tests against, just as they do with speed or intellect. It’s a choice, an option, a tool. - And not a reliable one!

The combat stat will typically be low: Around 30-40, the lowest being 26 and the highest being 45: being a d100 system it directly showcases the odds of success (or failure). A signal that combat, when tested equally and up to the dice, tends to the losing side. A marine can add +10 to that, but still only just barely crossing over the threshold of 50/50 if they rolled lucky (2d10 = 15 or higher). Even then 50/50 isn't anything to stake your (character’s) life on.

Then there's the double page for guns, and its clear combat is designed to come up, at least it’s promising that it will. You don’t provide weapon stats if you don’t expect players to use them (...or well…just hold onto this thought).

This isn't surprising, even Alien, a tense atmospheric horror, had combat (the flamethrower in the vents or when Ripley fights against Ash).

Then there’s the Marine. A class based around combat, but just as much based around roleplaying the military dude (Or maybe a Security Guard or Mercenary: There's a hidden flexibility in the trappings of Mothership’s classes)

This, I feel, can already hurt some player expectations, promising them they get to play a cool badass marine, will providing them with a horror and threat focused ruleset, Astute or Genre Savvy players may see it for what it is; a more defensive class, and one about causing issues through their want of fighting not running away, but this could certainly be better illustrated. (Those familiar with Aliens may recall how quickly all the marines were decimated, leaving the teamster (ripley) to fight)

But there's also an element to the marine that reaffirms combat as a choice and a tool. By having “the fighter” you expect the other classes to not fight as much, or suck a lot more doing so. Almost taking advantage of something that's an issue in DnD (where the fighter and the thief are classes doing what they all already do). The Scientist is about information; The Android is about technology: and the Teamster is about a little bit of everything (but certainly machinery and repairing).

Mothership’s Violence is explained to the player on PG16 under “how to be a good player”

“If you're fighting you're losing” - “Violence is deadly”. This all sets the tone, and the stage for how Violence plays out in Mothership. And the section about the dice already matches what we know about combat as a stat.

On page 26, It goes on to explain:

“Violence should be avoided” matches what the player may assume from a Horror and NSR game, but the emphasis on “incredibly dangerous” - None of this is particularly surprising.

Something to note is the core difference between Violence and Combat: but that involves understanding the difference between Combat (the play space) and combat (the PC action). In DnD (or your average OSR elfgame) Combat is the play state of engaging in a fight / facing off against enemies of some kind. Often marked by a roll for initiative, you may attack in combat, but you can also heal in combat, or cast a spell in Combat. In Mothership, instead of Combat you have Violent Encounters (or simply Violence). Marked by an active Threat intending harm or worse (there's always worse in a horror game). You can shoot in a Violent Encounter, and you can also flee in the Violent Encounter, or you can hide in the Violent Encounter. This means that mothership reframes combat as just an action players can take of many, and a risky one at that, but the core focus isn’t doing said combat but surviving the Violent Encounter. A perfect fit for a horror game where the PCs are intended to be outmatched, and the core aim is to survive (at least survive long enough to save or solve).

As an aside, You could argue that such a style would fit the OSR mantra of “avoiding combat” better than games which have a large combat section (at least proportional to the rest of the system)

With these expectations; of Violence not Combat, it being deadly and punishing, it being best avoided, of combat as one action of many, of the focus being surviving not killing; lets look at the actual core rules themselves.

Rules and procedures:

This is where the meat of Violent Encounter rules come up, structured in three parts: the rules, an example of play, a list of what can be done during Violence.

The core rules are listed under turn order:

Lets break this down:

A round is 10 seconds, every action happens at the same time (not turn based like DnD)

The Warden highlights ‘the situation’ and the risk of what is likely to happen if no response (Threat)

The players respond on how they individually Act

The Warden responds highlighting the Risks of each action failing

Characters may change actions, or proceed

Then all players roll *simultaneously* in a wonderful display of chaos

The Warden, utilising the rolls, sets what happened, utilising the set risk. (Resolve)

This Restarts, with the Warden highlighting the new situation (Threat)

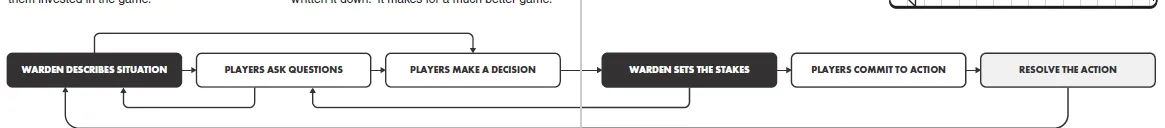

There’s a clear cyclical procedure here:

Threat - Act - Risk - Resolve - Restart

That’s simple, and illustrates exactly how a Violent Encounter should work; which also illustrates that most of the rules are here! We may have some questions, such as how does a Warden decide on the risks, and what does a player roll, and does a Warden even roll? But the fundamentals are here as you expect.

As for this procedure itself; it's fantastic for a horror game, by establishing an overpowering threat that PCs must respond to - with the grisly knowledge of what awaits them if they fail. It portrays a terrifying sense of a lack of agency, and provides great tension. The truth is however that players are not actually without agency. In fact this entire method helps inform player agency through giving direct and actionable information: Giving information to players is crucial for informed and thus interesting decisions and this procedure bakes that into itself directly. This is further exemplified by players' decisions being met with a discussion of the risk, cementing good GMing (Wardening?) technique as a core part of the system (exactly what mechanics should be doing). This also just reinforms the horror and the fucked positions of PCs. “Yes you can shoot your gun but you will still get attacked by the alien’s claws”. It becomes this or that, hard choices, with interesting opportunity costs. Then there's the “roll all at once” which adds a beautiful chaos emblematic of the situation the PCs find themselves in when a Violent Encounter comes up. It's wonderfully narrative focused, which is exactly what you want, where the focus is hard player choices arising from the fiction.

Most importantly however this entire procedure gets rid of any “nothing happens” results that prop up in similar games. See this is interesting, in many games i hate rolling for hit and then rolling for attack. I much prefer autohit (a.l.a into the odd and its ilk). The entire endeavour feels needlessly bad, and results in situations where you succeed, but your damage does low or is absorbed by their armour and you might as well have just missed, and the entire thing is hard to narrate as a GM. But mothership is about being down on your luck, and if your using your weapons your either cornered, suicidal or feeling good about your chances: on top of this weapon damage often uses multiple d10s, curating a bell curve of damage, than outright swinging. Primarily a bad situation, poor dice luck isn't a feels bad, it's a “genre doing the genre” thing. (and it goes to highlight how the OSR playstyle can fit horror well, and maybe not fantasy adventuring that great). The other aspect is because risks are already set, you never have these moments of nothing happening; a failure always pushes the fiction forward, and a success on the combat stat means you still avoid those risks even if your damage roll itself is bad. (and the damage roll anyway is a randomised timer of how long does the monster stick around, and often you'll be utilising it as a means of defence, or scaring it away, all of which succeed on the roll regardless of dmg dice).

But here’s the big issue of this system: It's new, but presented with familiarity. It's a single simple piece of text that explains itself but never reaffirms what it's teaching in a varied format. A flow chart here, like ironsworn’s or blade in the dark’s, would be excellent, especially for a more “mechanical” feeling to a rather structured narrativist procedure. It’s not unheard of: Quadra’s warped beyond recognition even has a flowchart for the usage of it’s powers (a great module i highly recommend, even if i spilt a cup of tea over my physical copy in a display of god’s ironic humour, as it now thus lives up to its title)

So what would a flowchart for mothership’s violent encounter resemble?

Simple right?

We can probably simplify each box easier as its for reference, each step an easy to remember phrase: Threat. Act. Risk. Resolve. Reset

So let’s see if the rest of the rules follow this or if we need to modify it further!

There's a brief section on using fear saves for surprise. This “players go first until surprises fuck them up” is familiar, from games like into the odd. Lets add that to the flowchart (Okay you can see I already have i just cropped it out)

Then, next on the same page, we get to this weird little box:

The strict turn ordering is our first hint at some confusion: well, this isn’t directly that confusing, but presenting an optional way of play, especially one that heavily affects the horror and tension being crafted, directly after explaining how to play, is confusing. This would be better placed amongst the difficulty settings on page 52 of the Wardens Operations Manual.

This entire text box too seems only to be there for DnD-players, either 5e players (as a game wanting to be suitable for introductory play) or OSR players (as a descendant of that culture of play). It shows a lack of confidence with its VE rules that does not match in tone with the rest of the zine, especially as the book already differs itself in so many other ways.

When teaching a new procedure of play - a new way to do “combat” - offering the players the means to play the way they already do hurts your game; it destresses the importance of the design choices made, especially as many players will lean towards what they know, and fundamentally experience a worse (or at least different) game, one better less suited to the experience aiming for. This is especially true for audiences prone to ignoring or misunderstanding the importance of rules in ttrpgs.

A lack of confidence also hurts its strength here: a more freeform style of play where you engage threats is strong and narrative, reforming the role Violent Encounters play in sessions: as challenges of survival.

Regardless , the design here is nice: a box clearly illustrated as an optional mode. Easily skipped for the second most important part of this page, and unfortunately something that is also typically skipped over:

The Example of Play

The example of play on page 27 is titled ‘The thing that was Phil’, a rather fun read of a PC-turned-Monster attacking the other two crew members:

The set up alone perfectly illustrates the horrifying nature of Mothership’s Violent Encounters, more importantly however it reaffirms the procedure we were just taught in the turn order rules:

Warden highlights the threat, including the risk of what happens if they don’t act (Enemy attempts to grab them both, and if it’s unimpeded will crash into them)

The players decide how they want to act, with the Warden highlighting the risk of those actions (One unloads her gun, and risks blowback damage from pipes. The other attempts to run, and risks being caught)

Note only one of the players is engaging in combat, the other is trying to get out of the way

They both roll at once

They take damage immediately from failing. The Warden never makes any kind of check for this on the monster side, they simply realise the threat they had already detailed.

(as a side note i love the way this is written, as a story unto itself. It's fun!)

But questions do arise typically on the Warden’s side:

Why does Cleo only risk getting blowback damage? How does the Warden decide this?

Why does Knox get caught on failure but Cleo doesn’t?

But both of these are Warden knowledge questions and this is the player’s survival guide, so we will wait and expect them to be answered in the Warden’s Operational Manual.

On the same page is a section on what you can do in a Violent Encounter:

Note the first mention of ranges - Being able to step into close range; then you can do one thing. Also note it states “generally move” an allowance for situations where this may not be the case: In a sticky situation (literally) or pinned by the monster.

The list of actions is extensive, with attacking being only one option of many: Interactions with objects or environments are especially highlighted.

Then the stinger on top: If you decide to do nothing other than run, you can move somewhere into long range: explicit rules for running away makes common sense for a horror game, but more feels like a whisper from the designer “hey, use this”

Then there’s one more box: being effective in a fight

Here it highlights that your combat stat isn’t the only thing that matters, as we had already ascertained from the rules so far. It emphasises using underhanded tactics because “Outsmart, outrun and outlast your enemy. That's all that matters”. Killing isn’t the aim here, although it's not unadvised either: it's certainly one way to outlast.

The format of this box, akin to the strict turn order option before, seems to function primarily as a reframe to the dnd crowd whose expectations may be killing first; Unlike that previous text box however this is written with confidence. A solid declaration: Violent encounters are about Survival not combat first and foremost.

After the page on Violent Encounters it discusses the rules on attacking and wounds, the book-keeping of VE. The page on wounds and death highlights the severity of damage in this system.Then there's dying, the death roll of which is another incredible element of tensio into the game…I won't ramble just go watch this Alfred Valley's video.

The pages after that is where we get to ranges.

Page 30 to 31 has a double page spread on Range and Distances, an abstract system that offers the adequate level of usage for both players and the Warden during VE and beyond them. Ranges are abstract framed primarily around how close to the thing enacting violence you are (or at times whatever you are trying to get to, or shoot ect.) This works splendidly with the already narrative Violence procedures, but hidden amongst these pages is the first stem of a little confusion that will run through out:

[For the sake of transparency and information clarity (since that's what I'm critiquing here!) I will discuss this here, but just be aware that even after reading through the mothership PSG at least over ten times, i kept forgetting where it was mentioned to use enemy stats for rolls. I knew it was mentioned somewhere, I scrubbed through the WOM and the UCR before I finally found it again on yet another close read through in the PSG. It's in a very strange place]

]

It's a short one but its placement is already odd. As I've already mentioned, examples of play are typically skipped over, especially one placed in the midst of rules.

And notice the confusion here: This mentions using monster combat stats. We haven't been introduced to them at all yet.

Then again it’s, it's not that shocking. Anyone picking up the boxset is flicking through all the zines for a glance before they read the PSG, and they’ve probably flicked through a module too, they know monster stats exist. However the PSG have not mentioned them at all until this point… and SPOILER they don't again.

Look at our flowchart:

The GM has a few steps on this procedure! But not once do they roll for monster stats, neither in the text of 26.1 Turn Order, nor in The example of play: ‘the thing that was phil’. It's even more transparent in the example of play, they never narrate the GM rolling for The-thing-that-was-phil’s actions.

But monsters do have stats, and quite a few of them. So let's relook at what this awkwardly placed text box says.

It's short, but we get this: The Warden rules on common sense that “just dropping a grenade not throwing it” requires an instinct check for the enemies on if they avoid it.

I immediately ask why this is not a check for the player, but it does answer that: If it was thrown, that would be a check, probably strength, for Cleo, but most likely at the risk of running. (Testing player ability) But since it was dropped, Cleo focuses on running, instead you are checking for enemy behaviour. Almost more like an oracle for the Warden to understand how the enemy responds. It seems you either test player ability OR enemy ability never both. Although this is a small segment to infer all that from, more detail would be greatly desired.

Thankfully, we've stepped into discussing a lot of Warden side of things already (and hey that’s the side I'm mostly coming from in this game) - Luckily there is a whole zine for wardens stuff, a great book full of advice.

They must go into how monster stats work in greater detail, right?

The Warden’s Operation Manual (WOM)

This book is great. A zine full of advice to start your first session with practical at the table information. Rules on constructing horror sessions, and gaming horror itself. The omen system is great, the discussions on safety are perfectly managed, and we love discussions on fail forward. The real highlight in my opinion however is the NPC framework, an incredible tool.

But all of this means that any glaring omissions sting all that much harder. I dont care that Mork Borg is missing rules on how to play it’s enemies, because it doesnt have rules for fucking anything on the GM side (okay i do care but thats me): That game is clearly not for first timers OR trying to do too much new (at least in mechanics). But Mothership is clearly trying to present itself for a new audience, for first time GMs, and first time horror GMs. This can be clearly seen not only in the WOM but also in the included adventure module Another Bug Hunt, an adventure which teaches one how to read adventures and modules, an incredible tool really.

But we are jumping ahead: Lets see what the WOM has to say about Violent Encounters overall:

The first mention of Violent Encounters appears on pg 10, in Something to Survive:

The bulk of this is advice on to not overly rely on Violent Encounters, warning against an over reliance, and to use them sparingly, before illustrating the variety that can be found in the definition of "Violent Encounters”

This matches with the PSG through how theViolent Encounters are only a small section of the overall book, and this is true of the entirety of PG10. It illustrates what other kinds of encounters you can utilise as a Warden in Mothership.

Psychological Trauma

Social Pressures

Environmental Hazards

Resource Scarcity

This rarity of use for Violent Encounters stresses how dangerous and thus terrifying they are meant to come across as, which fits with the threat first procedure, while also showcasing it's not the only source of danger. It's actionable advice providing the answer to what to focus on instead. But that begs the question if Violence in mothership is designed to be used sparingly, why am i putting all this effort (free, unpaid for effort mind you) into this? …Let's move on quickly.

The next page over - pg 11 for anyone who can’t count - is a list of tactical considerations to create interesting encounters. This stresses the puzzle solving nature of encounters, once again taking the focus away from full on aggression and getting the enemy hp down. Neither is this just limited to violent encounters: “Stealth Mission” could be moving silently past an enemy to avoid violence happening (because you know, violence is risky and scary.) In my own games I've had players sneak past a sleeping jaguar, because a jaguar attacking on a closed spaceship is pretty much a big issue.

Fundamentally this table is a handy warden reference to have, owing to the fact it appears on the warden screen too.

PG 20 is where it ends a section on creating a scenario, highlighting how to curate “something for everyone” aka. Making sure each individual class lives up to its potential. Here it talks about how the “marines are killing machines”

Hey it even directly calls motherships combat Brutal! But the advice here is interesting; The marines should look like natural born killers. (can i say i fully listen to this as a Warden, and not utilise the marine class as a joke on the military? well…) - But, like most of this book and unlike many others it follows it up with actionable advice: "Interpret their failed combat rolls more generously than others” - The idea here is one of player agency, making those who chose the marine class not feel like they fucked up doing so, and meeting the player with what they desire from the game.

This also answers a pressing question from earlier: Why did Cleo shoot pipes and suffer less damage, while Knox gets grabbed? Because Cleo is a marine, she tried doing what she does.

Is this the best warden advice? I don't know, it seems to me arise from a confliction of a “badass military” class in a horror game, but fundamentally in play i have found marine players feel successful enough in their class just having the opportunity to fix guns, or blow off doors, and other non-violence focused applications of the military skills. But that's also part of how this game plays; using a hammer to saw wood with. When shit gets bad you use what you have to the most of it. (which hey fits horror!)

Skip some pages and we come to warden etiquette, a mirror to “how to be a great player” we saw in the PSG. This is mostly general advice, but the point applicable to Violent Encounters is on rolling in front of players:

It's good advice, one I always do. It's once again about providing information to players so they can make informed decisions. We saw this in the example: ‘run away’, where the Wardens told the players what they were making (instinct) and why. Then it makes it more prominent that in the example of play: ‘the thing that was phil’, the Warden never rolls.

Page 26 on 'how the game works' is interesting for we finally get a flow chart!

This has wider application for the entirety of the game, and goes to show how Violent Encounters follow the same flow as everything else and dont serve as its own 'mini game'. However I see little reason why this isn't presented to the player aswell nor provided on the gm screen/rules reference for play. Otherwise its great.

Compare to my own flowchart constructed backwards from the Violent Encounter rules: It follows the procudure in the same way, with a core difference - mine is simplified as it is designed to remind a warden/player of the flow of Violent Encounters, and yes specificly focusing on Violent encounters, where as this is designed the entirety of the game and it's purpose is to explain and illustrate firstmost. I also find it's format, spread across two pages, harder to read, and would have preferred this being illustrated again in a one page format, and closer to Violent Encounters to reaffirm they utilises the same format.

PG 30 is where we get setting the stakes:

The main focus on failure; This matches what we know as the role of the Warden in the rules and examples of play so far. The Warden narrates the outcome of failures, this specifies exactly HOW to do that.

The three next headlines show this

- What are the plausible outcomes?

- There’s more than just success or failure at stake

- Informed decisions lead to better play

All of these we have inferred so far, but they develop this into a core understanding of the Warden’s roles:

- Outline possible outcomes of failure

- Highlight the possibility of success or failure, OR the extent of failure/sucess.

- Providing information to the players.

The last, informed decisions lead to better play, is something we have already discussed primarily that the Violent Encounter procedures do this by default, prioritising information to heighten player choice. This section even highlights that failure does not ruin the surprise, especially as players can weigh the risks. I'd go farther and say it’s also a great, natural source of tension when a player decides to take the risk.

The final heading on this page, ‘You’re all picturing something different’ discusses a reason to set stakes, so everyone at the table can be onboard, and gain a shared understanding.

At the end It highlights that:

This confirms the focus is on the conversation between the player and the warden.

This advice is not limited to Violence, in fact it has much more core wider application than the majority of what we have looked at so far. The provided example on this page refers to leaping to a ledge, the Warden highlighting a failure can be falling to death. This example also notes using the percentile system for varying degrees of failure; “if it’s close. Like 5-10 points, you’ll catch the ledge and be hanging off.” Then it shows the player choosing to do something different.

The next page, 31, focuses on Player Agency. This just repeats what we know, but importantly, that players have control over their actions and those actions have consequences. But this reaffirming of what we have already understood is key to learning how to GM Mothership (or GM at all). This repetition however becomes stark when key questions are ignored.

[the last heading “a good story only happens in retrospect” highlights why a NSR-style game can be a good fit for horror - It also highlights why a sudden death (although one that per the rules is forewarned and highlighted beforehand) *is* the story. I like the framing of this through a sense of *bathos* which is, imo, is the defining differentiation between this style of play and any others)

A textbox on the side doubles down on this, providing actionable ways of providing Agency. For the sake of Violence the most important one is:

Reaffirming the "violence is brutal” iterated several times in the PSG, and to meet the consequences.

Page 31, resolving the action, explains when not to and when to roll dice. It, like a lot of this book, is good advice but it’s noticeable that it has a very player focused language.

It also never outright states a Warden isn’t rolling dice, but neither does it confirm when the Warden may. The focus lies squarely on the warden adjudicating when dice should be rolled.

Page 33, interpreting failure, starts with an interesting point

This once again reiterates on what we expect with the combat stat, but this once again is very player focused. If that is what player stats represent, what do enemy stats represent?

Then it explains and explores what failure is… For any experienced GM or Player this captures the maxim of “failing forward”; that even on a binary roll system, failing a roll “doesn’t even have to mean failing to achieve their goal” with a stress on a bolded piece of text that states: “Every Roll moves the game forward, whether that’s for better or worse”

What that looks like is explored fully here, usable guidance for the Warden, which while it does ask for them to adjudicate to a degree on player rolls (something I'm not a personal fan of) it does provide a useful degree of information in the form of a table.

It breaks down the outcomes in four possible ways

1. Action succeeds, but costs more time and resources

2. Action succeeds, but causes harm

3. Action succeeds, but leaves the player at a tactical disadvantage

4. Action fails and the situation gets much worse

It provides three examples of each - an example for each result directly relates to VEs

1. Player fails a combat check to shoot an adjacent enemy - They hit the creature, but it costs all their ammo

2. Player fails a combat check to shoot an enemy at close range - The player gets to roll damage, but so does the enemy

3. On the run from a pack of gaunt hounds, the player fails a strength check to open a stuck airlock - The player is able to open the airlock but gets stuck in the process. They’ll be able to get out on their next turn.

4. The player fails a combat check when firing at an enemy in a crowded corridor - The player’s bullets ricochet and everyone in the party must make a body save to avoid being hit.

This clearly illustrates the expected level of dynamism in mothership’s Violent Encounters, showcasing that more narrative bent we saw from the initial procedures.

It’s not the only piece of information here designed to make the role of the warden easier (if not codified) - It states that the game was designed with a d100 system so the warden would have room to interpret.

Something to note here is how the procedure of the VEs already parcel the idea of everything moving forward, with continuing through with your threat a priority that eases the burden of adjudicating player rolls, and with the scene, goals and risks highlighted already there is more guidance to interpretation of rolls. (It may or may not be a criticism of the game that it requires an element of GMing skill to play to its best, however it cannot be denied that the game goes to lengths to teach you those skills, ones transferable to other games)

Page 37 is the page for Violent Encounters, But the page it's coupled with, page 36, covers Social Encounters. This suggests they exist as two sides of the same coin, and why not? An npc, who you can talk to or befriend can just as easily be a threat, or the monstrous alien who has been a threat so far may turn out to be an aware talking being you could attempt to socialise with; that blurring of the lines is a core part of horror, but also allows choice in how a player interacts with them.

Under social encounters is one salient line:

But the most important piece of information we have received yet for the Warden running Violent Encounters is at the top of page 37:

This emphasis relates back to that narrative style of Violent Encounters; The focus is on the dread and how the characters react and suffer, not on the tactical mini game. This is a direct explanation of what the core of Violent Encounters in mothership is; Just as DnD 4e or Lancer does focus on that tactical minigame. This game is this and not that, is the confidence we want to see in game rules. This also allows us a lens through which to judge the effectiveness / design of Mothership’s rules, primarily on if they create the feeling of disasters happening to people in real time. (as there is no such as thing as good or bad design, but design fit for / effective with the games intended goals and/or its promises of play)

The rest of this page covers more Wardening advice - not unexpected in the Warden’s Operational manual - and good advice, but it’s sparse on actual rules or procedures for the warden.

The subheadings cover:

Every Monster is a boss monster (they are not obstacles to be overcome)

Never say you miss (as seen with pipes bursting the-thing-that-was-phil example)

Every Violent encounter is the worst day of someone’s life (intelligent beings try to de-esculate or escape)

Smart Enemies are deadly enemies (don't treat them as a bundle of numbers)

Defeat doesn’t always mean death

The first is interesting, the warden side of “don’t aim to kill the enemy, aim to survive the enemy” - a good frame of reference for the would be warden.

The third is the first sense we get of the Warden’s role in truly bringing enemies to life, roleplaying them and realising them in the narrative of the game. This is doubled down on in the fourth subheading, when it explicitly states not to treat them as a bundle of numbers. This is good advice generally, but somewhat baffling. Mentioning creature stats existing but eliding what they actually do. If the aim is to roleplay the enemy, change tactics, set traps ect, then what do we actually do with the enemy stats?

This page doesn’t answer this. There's a hefty text box on death, which reinforms the deadly nature of Violent Encounters, before the last entry states:

So enemy actions happen by default; that's explained and reinformed in the players survival guide - failed rolls move the enemy forward and the players back - this is genuinely good advice but it still doesn't explain how we use enemy stats. How do we use an enemy's multiple attacks or weapons effectively?

Instead it explains that we can switch to “player facing rules” in the difficulty settings for a “real challenge.” Wait, what? The text just explained the core rules ARE player facing; that enemies don't roll but happen by default. - So what does that mean?

But before we go there I want to look at what we just read; We have exhausted all rules in regard to Violent Encounters; The following pages cover other aspects of the game, such as 38 which covers investigations. This is good! Violent Encounters are designed to be rare, a lot of the game being slow tense build ups (but tailored to what the group desires). However we have not received any actual rules for the warden as to how they mechanically interact with Violent Encounters. This is not so much an issue, it suggests their role is fictional positioning, adjudication of rolls, and roleplaying the enemies; but the existence of monster stats suggests a mechanical focus completely ignored in the WOM - Maybe however this is finally explained in the Unconfirmed Contact Reports?

But before then… Lets talk difficulty settings:

One pg 52, under ‘customizing your campaign’, is various information on how the Warden may tailor the game for their group, such as utilising skills as a wishlist or creating new skills. Its speaks to changing the difficulty too through optional rules and provides a list as an example:

Okay, a list of ways to tweak the way the game is great - It showcases the customisability of the ruleset while also providing examples of how you would go about doing that. I’m personally a big fan of High Score Breaker and Impenetrable Wounds, ones I use at my table.

But there is a glaring issue; 13th (ironically) down the list is “Player facing rolls”

This is a glaring bit of confusion. Its stating that player facing rolls are an optional difficulty setting; However the game already uses player facing roles - “Players make all rolls” but the only rolls we have seen the Warden make, was one roll for the enemy out of combat. We certainly don’t know the normal frequency in which the Warden rolls, but every example of combat had player facing rolls baked in. “in violent encounters, a failure to hit means a character is hit instead” - Okay this is slightly different than what we have seen, but worded awkwardly. If in a normal Violent Encounter you can attempt to hit, miss, and *something gets worse* this could be suggesting instead that every time that's being attacked by the monster - but that isn't adding player facing rolls that's just increasing the amount of attacking by the enemy, as the core rolls, as we saw earlier already cover this in regards to failures being a success with a cost, OR a failure and things get worse. It could be suggesting to not describe the immediate threat, and instead decide after players act - the monster being only reactive, which would certainly tweak the difficulty, but that isn’t expressly clear here.

Regardless the setting itself doesn’t matter, but its inclusion does have the effect of people seeing “player facing” and assuming the core rules do not use player facing rolls, despite the two core examples of Violent Encounters not requiring any warden rolls. This is a source of confusion exacerbated by the lack of clear information on when and where to roll enemy stats.

With no usage to how to use monster stats, except for one example of play, then we can assume they must be where the monster stats themselves lie; In the Unconfirmed Contacts Reports. Right?

The Unconfirmed Contact Reports (UCR)

No. They explain how to read the stats but never how to use them. The UCR, while being a great read (and somewhat nostalgic as someone who accidentally stumbled upon the gumshoe Book of Unremitting Horrors as a scp-loving teenager) mentions no more on Violent Encounters… That sucks, and with the only other book being The Shipbreaker’s Toolkit, we can safely know we won't ever patch this glaring omission.

So let's look at these stats in question:

Combat is the first stat, followed by its attack[s] and damage value[s], showing the importance of enemies stats in Violent Encounters. The attacks and their values, naturally will be used, but there is no defined usage for when combat stat is utilised. In what we have seen enemy attacks happen as a threat highlighting what they will do; in the UCR it states the combat stat is “the horrors ability to fight and defend itself” - We know this isn't rolled for IF their attack will succeed or not (like some other games) but it may be used in situations when a player isn’t affecting it - as a tool for the warden playing the horror. Ie. Does it slaughter this entire room of helpless NPCs in one turn or more? Does it break open the elevator doors? - On top of this if we accepted that enemy rolls combat to attack after players make their moves (against what is stated in the VE rules and examples) then that mitigates a core element of the rolls; meeting the threats, and also turns into a system where rolls can lead to “nothing happens”which is explicitly against the aim of the system. (Eg. If a monster is going to attack Lilly if she doesn't act, Lilly attempts to jump out of the way, but fails. If the warden then rolled to attack for the enemy and it failed, what then? Why does it fail? What is the cost of failure to Lilly's roll?)

Enemies can have several different attacks (or weapons), some even incurring special rules either as a separate attack or linked to ones. There's not any real explanation of how or when to switch between them, some Wardens may find themselves afraid to utilise a special attack seeing it as choosing to be harsh, then again as horror and the rules clearly prioritising informing of all threats, there's little reason to do so. Regardless, some support for when an enemy may utilise a certain attack could be helpful; this could prompt a combat (or instinct, see below) check to see if it chooses to use its special, but explanation of this in the rules would be better.

Enemies also have Instinct - this is an interesting piece of design, a catch all for all stats so you don't need to evaluate the speed, intelligence and strength of every horror, but they can still be separated if they have a noticeable quality in one. The issue is this is pretty mitigated when we don't know how to use these stats, especially in a player facing system. - like with combat they can be utilised when they don't affect the player, like if they can catch an npc before they reach the elevator, but what about when a player is running to the elevator? Do you use the creature stat, or the players? Is it a contested opposed roll in some way? Do you just compare stats and whoever has the highest wins? If it's the players then an enemy’s high speed stat won't be incorporated into the fiction, and if it's the enemy’s then the player may feel without agency. We see in the one mention of using enemy stats that it can be based upon the fiction, where it's because it was dropped and not thrown, the monster being the active proponent not the player who chooses - which is why i used running away, both actors are active in that situation, and this too isn't clearly explained, the idea of an “active” proponent is one i am inventing based on an interpretation of one example of play (which many may have skipped over) - The inclusion of stats in the system suggests a desire to make each monster feel unique at the table, which would also make sense why a player facing option would be offered but not be the default.

Personally I can see a work around, but the fact of the matter is I shouldn't have to, The game should have explicit information on how to utilise enemy stats. The entire point of this is not to provide fixes or interpretation, but to examine what explicitly the rules say. The flowcharts i have made so far are explicitly the Rules As Written (to stipulate a stubborn point)

But fuck it lets break from that and look out how to fix this:

How to Use monster stats

The immediate way i see is looking as i have at the example of play, which as I've explained already is looking at the Active proponent of play:

When deciding whether to utilise player or enemy attacks, decide who is providing the core action to be tested. [eg. Is a player throwing a grenade and thus testing their aim/throw, or is the enemy avoiding a dropped grenade and thus testing their reaction?] - these tests work best as the result of a hard choice [Warden: if you throw this grenade you will have to slow down and make a speed check or you can drop it while running but the creature gets to react]

If both the enemy and the player are providing actions being tested, [Eg. A chase where both parties are running] roll for both; If both succeed the highest value wins, if one fails the other wins, if both fail both incur penalties or something worse happens [a creature and a player both failing speed checks, the creature may slam against the ships window and cracks start showing]

Of course you are only rolling if failure is interesting.

This is a rough go at it, and you may have your own way of handling this but it's an example of the kind of information mothership is missing. There's another facet to this; I've only been looking at Violent Encounters; the enemy stat lines can serve an Oracular fashion in general as we have explored already.

Enemy stats can be a powerful oracular tool helping the warden decide how an enemy behaves. When it is not obvious, the combat stat may be utilised to check if the Void-Crab is aggressive or not, or you may check intelligence/instinct to see if the Angry Android thinks to shut off the power. It's a roleplaying tool for the warden.

This is the Solo Player inside me, and the fact as a GM I like to be surprised far more than decide upon things. You could even use the combat roll to decide how many people get attacked. In fact my solo rules for mothership themselves will utilise the combat roll to decide enemy actions - ‘Isolation Kills’ utilises enemy stats in the oracular fashion described above but as a baked in part of the procedure. [One example; faced against three weird purple crab-aliens I rolled to see how many attacked me immediately. They had a low combat of 30, but all three succeeded, jumped at me and ripped me to shreds. It was fantastic, a piece of stellar scifi horror storytelling that arose from the system.]

The confusion

So we have already identified some core elements that cause confusion

- Lack of codified explanations/guides for the warden

- Lack of explanation regarding Enemy stats usage

- Confusing contradicting language in the difficulty settings sections

But I don't think these are the ONLY reasons, but these certainly reinforce other issues. Other reasons why people may be confused:

1. Assumptions / Baggage from other games

2. Concerns around balance

3. This relies heavily on the GM

4. Creator confusion

1. Assumptions / Baggage from other games - Mothership smells a lot like any other OSR [or NSR, i guess] game: it has dungeon crawls disguised as ships, and it's preoccupied by resource management and puzzle solving. The combat, a typically codified unchanging element of OSR games, being radically different - reframed around violence - trips people up, wondering “when does the gm roll?”. Like it or not, I often forget that the player facing rolls in Mork Borg is seen to many as novel and new (it's not though, come on). But this is worsened by the rules of mothership not doing enough to codify and explain how it's played, a flowchart to refer back to in play is the easiest way to fix this, like training wheels on a bike, at least for the first few sessions of play. Instead they double down on appealing to this crowd (which stifles interesting design for more of what they know) with that optional box for fixed turns. This is a flaw of the communities and perception of communities (and designing for “playstyles”) rather than meeting the game where it is at, and mothership does differ in other ways (for one it has many ‘levers’ for the GM to pull upon). It’s a problem that arises from connection to the OSR community too, for bringing outside game knowledge of how to play is often core to how they design games (Going back to Mork Borg that game is impossible to play without doing this) - I’m not commenting whether this is good or bad to do, and i plan to examine this in greater detail at some point, but it certainly does effect the way people come into other games.

2. Concerns around balance - Often a pitfall for RPGs in general, but the lack of seeming balance is the entire point. It's not Combat, it's a Violent Encounter, a survival problem. But there is balance in truth, between the horror - the threat - and player agency, a balance of information and how to act upon that information. One enemy may be a tough fight, that showcases that several may be complete suicide and shouldn’t be attempted. But too the lack of “balance” can and should work the other way; The supplies and weapons players have can change the threat of certain enemies. (Mothership does need a better inventory system to really utilise this however, IMO)

3. This relies heavily on the GM - Yeah, this combat does rely on Warden ability: Part of that, as discussed, is worsened by the lack of solid tools on the Warden side, despite the solid advice the game does offer. My preference in games is towards ones that provide solid mechanics and procedures for the GM too. I much prefer to focus on description and creation than making sure I'm managing the whole table, but I like Mothership’s combat despite this. My reasoning is that often the situation and thus threat arises naturally from the narrative, and hence it being a horror game I feel no need to not be ruthlessly hard on my players, as after all the expectation lies on these situations being a core threat to the characters’ lives. Remember the games core guides on being a great player, which I personally read out every session I play, explicitly explains that violence is deadly and punishing, and the WOM illustrates that it should be rare. You established precedent for this, and the game structure already illustrates all risk of failure, by its structure always allowing a player to respond. This is fundamentally different from an enemy rolling initiative first then succeeding on an attack and then killing a player before they have a moment to think. (I hate in dnd and other tactical combat games where a GM playing strategicly is seen as “MEAN”, fuck off. I should be allowed to play the game too. In mothership, describing the ruthless onslaught of vicious enemies is playing the game for the warden, which the VE procedures play into perfectly). However I also understand the strain of this better than anybody by trying to work the combat into a Solo Toolkit: I want to mechanise the role of Warden.

Is this needed in a Wardened game? No, but the tools for an indecisive Warden would be nice, that or/and some guidelines towards playing enemies. In Isolation Kills I discuss adjudication, giving a simple structure for how to come down on a situation, following in order:

- The most interesting thing

- The worst thing for you

- The best thing for someone else

- The second best thing for you

(bear in mind this is very specific to mothership)

4. Creator confusion - So somewhere apparently the creator, Sean McCoy, has stated that the rules for VE does require enemies to make a combat roll. This is apparently in the discord. However apparently it's also stated he does play with the player facing rules in his own games. I say apparently because I am not digging through discord messages to find this, nor does what the creator say from four years ago in what is effectively a (public) group chat mean anything. This is why I purposefully laid this article out in this manner; To explicitly look at what the Rules as Written actually says, not what their author states they are. When looking at a game the only rules that matter - and will ever matter in five years time when discord is dead because of increasingly exploitative practices like skype before it - are those printed in the book. If the creators want to correct it, they can make a 2e (or maybe an official errata? Those are so common in skirmish games, but i never see them for RPGs?) - Besides its bizarre to say “The real rules are actually worse than the ones I play” like chill, let people think you're a good designer. More accurately it seems combat/violence, being the biggest change between 0e to 1e, went through a period of indecsion that lingers even after the release of the game.

The End

Mothership’s Violent Encounters are both well designed and poorly explained, luckily the latter is easier to fix.

Something to bear in mind is that mothership is designed as a scifi horror toolbox, hence its varied modules, by official and 3rd party. Whether combat is a core part of the campaign ala ‘aliens’ or ‘resident evil’, or if combat is a struggle designed to escape monsters with ala ‘alien isolation’ or ‘silent hill’, or if you give the players nothing to fight with and an enemy without HP, its upon the adventure or session you play. However, Violent Encounters, as long as there is something Violent, and that's 90% of Mothership Modules, Violent Encounters will occur, whether it's a crazed npc or a hungering slime beast or a rabid robot dog or space pirates. Do your players fight, run, hide, out-think or give up? That's up to the session and the fiction and the context, but mothership provides a framework that allows for this variety.

Then again who am I kidding, even for a rules light rpg like this in a smattering of small zines, the players aren’t reading the rules.

(and if yours do, fucking cherish them)

—

I do want to stress, despite everything I've said here I do love mothership a lot, flaws and all. I hope I've displayed the issues primarily lies in information of clarity rather than mechanics, a much more forgivable sin, and I've written this much because I want the game to get better, and I want others to play this game at its strongest without getting confused. Mothership is one of my favourite games; I wouldn't be hoping to one day get the deluxe edition to go alongside my basic box set, and to replace my 0e editions of the official modules, if i didnt love this game. (if such an act would ever not be financially stupid)

And talking about money: If you enjoyed this nonsense endeavor, feel free to tip me @ kofi. It would be greatly appreciated because HRT is expensive, this hobby is too, and this took 6 months of my time :) Thank you for reading.

The combat flowcharts created here can be downloaded here